credit: Chris Jordan

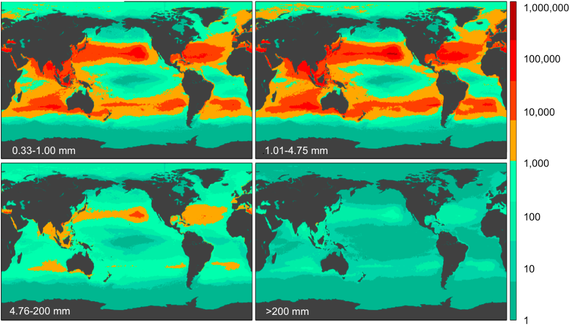

The amount of plastic in our ocean is rising. The flood of plastic detritus — from the large to the microscopic — swirling in our oceans weighs in at 269,000 metric tons, according to the most comprehensive research on marine plastic hot off the press today. One of the researchers, Dr. Marcus Erikson, visualizes it like this: “2 liter plastic bottles stacked end-to-end forming a column to the moon and back TWICE.” That’s roughly 6 billion bottles afloat on the high seas.

But as devastating as these numbers are, Erikson says they’re way too conservative. Given that we produce 300 million tons of plastic every year and the National Academy of Sciences estimates 0.1 percent of it ends up in the ocean, he says he knows there’s more. Way more.

So where is the rest?

Especially the most toxic and chemically laden fragments — microplastics — which numbered 100 times less than expected.

There are two mechanisms accelerating the marine plastic phenomenon: gyres, which pulverize plastic, and ocean currents transporting it to the ends of the earth.

Gyres operate at the ocean surface where we can easily see the mess. In the largest and most famous of these watery vortexes — the Great Pacific Garbage Patch — spins more than a third of all marine plastic pollution.

Driven by winds, gyres can suck in 20-pound plastic fishing buoys and shred them into tiny fragments. Ninety percent of the plastic found in gyres is smaller than a grain of rice or sand — the right sizes to be mistaken as food by hungry fish and other filter feeding marine life.

This is partly why the amount of plastic is lower than expected — the stuff has already been ingested into the food chain. Plastic is making its way from the digestive tract of minuscule zooplankton, up the food chain, one species at a time.

Plastic ingested by a Rainbow Runner in Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Photo credit: Marcus Erikson, 5-Gyres Institute

Additionally, once the shredding job is done, gyres eject plastic fragments. Some fragments get carried off by surface currents, others sink and can accidentally hitch a ride on another current — the great oceanic conveyor belt.

The conveyor belt distributes nutrients and oxygen throughout the world’s oceans by forcing warm and cold bodies of water to mix. This mixing also makes life on earth livable — if you recall in The Day After Tomorrow things got pretty frigid on the eastern seaboard when the north Atlantic part of the current shut down.

But blockbuster-fiction aside, the conveyor belt has become the accidental global distribution system for plastic — taking it not only far, and wide, but also deep.

Microplastics are now embedded in arctic ice cores. Erikson found plastic in 90 percent of the water samples he took from sub polar gyres. There’s plastic in deep-sea sediments, and washing up right now on a beach near you.

Beach in the Azores. Photo credit: Marcus Erikson, 5-Gyres Institute

If feeding your children fish fingers laced with tiny bits of plastic doesn’t sound horrifying enough, it’s the nasties that come with marine plastic that have some scientists calling it hazardous waste.

Endocrine disruptors such as phthalates are used as plastic softeners, pesticides like DDT, POPs (persistent organic pollutants), and flame retardants readily adhere to plastic. Meaning tiny plastic fragments are highly toxic — poisonous pills, if you will — swallowed firstly by unwitting fish and then by those at the top of the food chain. Us.

Erikson does think the tide of plastic pollution is turning. As we ban single-use plastic bags — one city, one state at a time — we are entering the Age of Restoration. He thinks if we can turn off the waste tap, and stop abusing our oceans they will eventually dispel all the plastic and heal.

He suggests looking to the waste-pickers of the world for conservation tips. Whether in Mumbai or Los Angeles, sorting through a landfill or dumpsters, waste-pickers follow the money. They bypass most plastic items only taking what has recycling monetary value — bottles with guaranteed refunds.

If a value is put on all post-consumer plastic, Erikson envisions less plastic poisoning marine food webs and littering our planet.

Captain Charles Moore, who discovered the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, goes a step further suggesting the ones making the profits — the plastics industry — should also bear some responsibility for recycling/clean-up costs. Much the same way as big greenhouse gas polluters are starting to do with cap and trade programs.

With more plastic produced in the first decade of this century than all the plastic produced in the previous 50 years — and production set to quadruple by 2050 — we’d better hope plastic debris gets downsized sooner rather than later.

To those who’re thinking couldn’t we just vacuum the plastic back out of the ocean, at 5.25 trillion particles and counting; the job is too big and collateral damage to marine life too probable.

Even Dutch wunderkind Boyen Slat, who crowd-funded $1 million in 32 days for his aeronautically engineered collection device for ocean plastic, now admits there are logistical limitations to his solar-powered brainchild.

Before we got so successful at utilizing fossil fuels — plastic is a petrochemical polymer — the ocean could wash away most of what we threw in it. But not at this rate.

Like other carbon-based products we have to reduce our dependence on plastic.

Fish is the primary source of protein for more than a billion people. Who will want to eat fish when they find out it comes with a built in side-dish of plastic?

This article was originally published on huffpost.com